by Thomas Kurz

This article covers requirements 9 and 10 for instructors. Requirements 6, 7, and 8 are covered in the previous article.

9. Explain the anatomical limitations of range of motion in joints of the spine, shoulder, and hip.

Range of motion may be limited by muscle tension, muscle length, joint structure (shape of bones and length of ligaments), and postural defects, which position joints so they can’t reach their full range of motion.

Tests of one’s potential to do a front split, a side split, and a back bridge

To see if joint structure as well as muscle length permit reaching the desired range of motion, perform tests of flexibility potential for front splits, side splits, and back bridges. These tests determine whether one has the potential to do front splits, side splits, and back bridges, even before beginning my strength and flexibility program. Articles describing the tests and additional articles on factors determining flexibility are listed below.

Difficulties with Doing a Side Split

Biomechanical Factors that Contribute to Rotator Cuff Dysfunction and Injury

Flexibility Problems, or Kiddie Stretches for Adult Joints–You Have to Be Kidding!

An Easy Way to a Side Split for Men Over 60

Splits at 60: Questions and Answers

Be aware of gender differences in ranges of motion, mainly due to skeletal differences between women and men. Universally women have a greater range of motion in the hip joints because of their wider pelvis and more compliant ligaments. Also, the lower back is better adapted to extending (bending backward) in women, for several reasons: Women have more wedge-shaped lower back vertebrae (L3, L4, L5) than do men (L4, L5), the dorsal areas of the lower back vertebrae bear a greater proportion of the spinal load in women than in men, and women’s lower back facet joints are more oblique, thus better resisting forward shifting of the vertebrae. These adaptations resulted from the challenge posed by pregnancy in the upright posture. They allow pregnant women to compensate for the pull of an enlarged belly containing a fetus by extending the lower back.

To tell whether one’s range of motion is mainly limited by muscular tension, see if the muscles contract in response to a stretch. If they do, it means that relaxing them can improve one’s stretch and that one should be concerned more with nervous regulation of the muscles’ tension and less with the muscles’ maximal length as determined by their connective tissue.

Now, limitations imposed by the structure of joints and by poor posture:

Spine—stenoses (narrowing of spinal canal or of nerve root canals); listheses (slipping of vertebrae)

Shoulder—the shape of the acromion; control of the scapula (function of periscapular muscles); posture (head forward, thoracic kyphosis)

Hip—coxa vara (less than 135° angle between the neck and shaft of the femur); ligaments of the hip joint; spine dysfunctions limiting lumbar mobility

Recommended article:

10. Know the consequences of developing excessive flexibility.

Adequate flexibility, or range of motion, permits performing one’s techniques in the most efficient body alignment and without wasting energy on overcoming tightness of the muscles and ligaments.

Flexibility is excessive when a person needs to exert a deliberate effort to maintain stability of the joints or even cannot actively stabilize the joints at near-maximal range of motion.

The best and most time-efficient exercises to prevent imbalances between flexibility and strength are those that increase flexibility and strength simultaneously.

For more on developing excessive flexibility, read the article Can You Have Too Much Flexibility?

Requirement 11 will be covered in the next article.

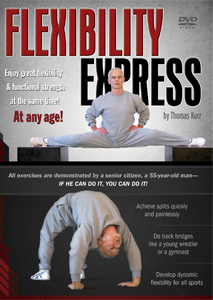

This article is based on the book Stretching Scientifically and the video Flexibility Express. Get them now and have all of the info—not just the crumbs!