by Richard J. Vahl and James B. Vahl

Information on this Web page is for educational use only, and is not intended as medical advice.

Every attempt has been made for accuracy, but none is guaranteed. If you have any serious health concerns, you should always check with your health care practitioner before treating yourself or others.

Always consult a physician before beginning or changing any fitness program.

Shoulder injuries are the most common upper extremity problem in the general population and in sports. These injuries can occur at any age but are especially frequent in the over 40 age group and among men. Rotator cuff impingement, tendonitis (tendon inflammation) or tendonosis (tendon weakening), joint capsule tears, and structural injuries are all common in athletes, both male and female. Athletes in contact sports and in sports that involve overhead motions are especially vulnerable to these problems. Injuries causing damage to the small and delicate rotator cuff muscles are the most common, are often debilitating, and can easily become chronic. Raising the arm overhead requires a fine combination of shoulder mobility and dynamic stability. Structural arrangement of the shoulder joint (more exactly, the glenohumeral joint) makes it highly mobile but prone to instability. Because of its structural mechanics, the shoulder joint relies heavily on support from the group of relatively small muscles collectively known as the rotator cuff complex. The rotator cuff complex enables the shoulder joint to produce its numerous movements while still maintaining a balance between shoulder mobility and stability. Normal arm motion is a product of:

- proper shoulder blade motion along the rib cage,

- balanced muscle strength and function,

- efficient neurological timing of synergistic muscle contractions, and

- integration of neural activity for feeling and moving.

Biomechanical Structure

Scapula, clavicle, and humerus

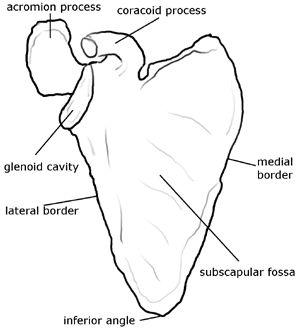

Scapula—front view

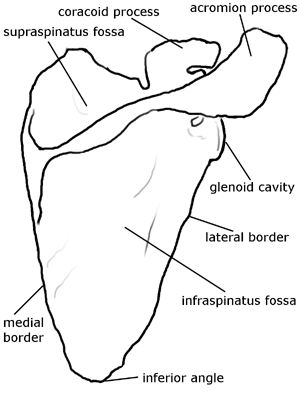

Scapula—back view

Shoulder and rotator cuff muscles—front view

Shoulder and rotator cuff muscles—back view

The primary role of the shoulder joint complex is to place the upper extremity in positions that allow the hand and arm to function. The upper extremity can assume an infinite number of positions in a three-dimensional perspective in space. This is because the glenohumeral joint (the joint between the head of the arm bone and the glenoid cavity of the shoulder blade) is a modified ball-and-socket type of joint capable of movement in all three cardinal and all oblique planes of motion. The shoulder joint complex does sacrifice some of its stability as compared to the hip joint for the sake of extra mobility. It has a very shallow socket and a small joint surface contact area as compared to the hip joint. So, instead of a fairly closed ball-and-socket joint like the hip joint, it is more of a golf-ball-on-a-tee joint. The humeral head articulates with a smaller and shallow saucer-like joint socket, the glenoid cavity, which is located on the anterolateral (front-and-side) surface of the scapula (shoulder blade). Therefore, the glenohumeral joint is considered more dynamically stable than statically stable. One of the major functions of the four rotator cuff muscles is to work in concert with each other to stabilize the humeral head as the arm moves. They do this while pulling the humeral head downward and inward within the glenoid cavity. The other functions are initiating, fine-tuning, and being main movers in precise movements (e.g., arm rotations).

Biomechanical Function

Since the humeral head is three to four times larger than the glenoid cavity, only approximately 25 percent of the humeral head is in contact with the glenoid cavity at any time. As already mentioned, one of the main functions of the rotator cuff muscles is to compress and depress (to pull in and down) the humeral head within the glenoid cavity, to prevent it from spinning, sliding, and rolling off the top of the glenoid cavity and striking up against the undersurface of the acromion process. Such uncontrolled movements of the humeral head cause injury to the joint’s surface, rotator cuff tendons, and all other structures that are between the humeral head and the acromion. Under normal circumstances, the rotator cuff muscles enable the humeral head to be constrained within a couple millimeters of the center of the glenoid cavity throughout most of the arc of the arm’s motion. The four rotator cuff muscles are:

- supraspinatus,

- infraspinatus,

- teres minor, and

- subscapularis.

These muscles all work synergistically. However, they each have an individual function as well: The supraspinatus arises from the supraspinous fossa of the scapula and attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus. Its function is to work closely with the deltoid muscle to raise the arm in flexion and abduction. The supraspinatus fibers maintain a horizontal line of pull, much like guide wires, which resolves or modifies the deltoid’s vertical line of pull. Weakness or extensive damage to the supraspinatus allows the vertical pull of the deltoid to drive the humeral head directly against the undersurface of the acromion process. When this happens, it is called a subacromial impingement. The infraspinatus occupies the infraspinatus fossa on the posterior surface of the scapula, below the spine of the scapula. It attaches on the rear of the greater tubercle of the humerus. The infraspinatus also has diagonal fibers. Thanks to the diagonal orientation of the infraspinatus fibers, their line of pull produces external rotation of the arm as well as stabilizes the glenohumeral joint by pulling the humeral head down and in. The teres minor occupies the upper two-thirds of the armpit border of the scapula. The teres minor, like the infraspinatus, attaches to the greater tubercle of the humerus and produces external rotation of the arm. The subscapularis is an internal rotator. It has a diagonal arrangement of fibers and, therefore, a diagonal line of pull, which prevents an upward and outward dislocation of the humeral head. It occupies the subscapular fossa on the anterior surface of the scapula and attaches to the lesser tubercle of the humerus. Force couples of the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and long head of the biceps brachii muscles create a concavity compression mechanism that pulls the humeral head into the glenoid cavity during all movements of the arm. In other words, rotator cuff muscles plus the long head of the biceps (which presses on the humeral head) keep together the joint surface of the shoulder.

Balanced Strength and Function

Balanced rotator cuff strength and function are necessary to prevent upward migration of the humeral head and subacromial impingement of the rotator cuff tendons. The supraspinatus and teres minor are considered the most efficient abductors and humeral head depressors in the rotator cuff group, respectively. As a group, the rotator cuff directs and stabilizes the humeral head within the glenoid cavity, while the larger extrinsic muscles, such as the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, and deltoid produce the forces necessary for gross arm and shoulder movements. Without this stabilization by the rotator cuff, gross movements of the arm would cause irritation, pain, and finally inflammation that would eventually destroy the joint.

Injury Mechanism

The most common injuries to the rotator cuff are:

- primary impingement,

- secondary impingement,

- degenerative anatomical changes,

- tendonitis, and

- rotator cuff tears.

Primary Impingement

Encroachment of the humeral head beneath the acromion process can reduce the shoulder space. This space, between the top of the humeral head and the inferior surface of the acromion process, is normally only 5 to 10 millimeters deep. It enables the rotator cuff tendons and their lubricating bursae to glide unscathed beneath the acromion. A reduction in this space can cause impingement or abrasion of the rotator cuff and of the long head of the biceps tendon.

Secondary Impingement

Scapular instability is found in two-thirds of individuals with rotator cuff problems. Poor scapular kinetics can lead to reverse scapulohumeral rhythm or a hiking motion during humeral elevation, which can lead to impingement as the humeral head is driven upward into the acromion. During normal or proper shoulder flexion and abduction, both upward rotation and posterior scapular tilt move the acromion process away from the greater tubercle on the humeral head, allowing the humeral head and rotator cuff muscles and tendons to move freely. Both the primary impingement and the secondary impingement may lead to more severe injuries, through irritation and resulting inflammation causing bone spurs, weakening of tendons, and rotator cuff tears. Rotator cuff tears are generally classified by the extent and depth of the fiber damage as either partial or full thickness tears. On the average, up to 40 percent of rotator cuff tears are full thickness tears, and the majority of them are asymptomatic. Factors leading to subacromial impingement and rotator cuff tears include the following:

- Acute sudden trauma

- Repetitive or cumulative trauma

- Anatomical variants in acromion process shape

- Laxity of the joint capsule

- Excessive tension or tightness of the posterior and inferior joint capsule

- Impaired sensorimotor function

- Improper exercise selection and technique

Other causes of injury and rotator cuff dysfunction include kyphotic posture with rounded shoulders and abducted shoulder blades, as well as fatigue and weakness of periscapular (shoulder-blade-moving) muscles and rotator cuff muscles.

Injury Prevention

Exercises for strengthening and conditioning both the periscapular muscles and the rotator cuff muscles, for joint mobility, for sensorimotor training, and for postural awareness are essential components of both a rehabilitation and injury prevention program.

Rotator cuff and periscapular muscles

Rotator cuff and periscapular muscles

Rotator cuff and periscapular muscles

Periscapular muscles

The periscapular muscles are:

- serratus anterior,

- pectoralis minor,

- levator scapulae,

- rhomboideus minor and major, and

- trapezius.

These should be the initial focus of a proximal shoulder stability program. Normal scapular motions against the rib cage provide the stable yet mobile supporting base from which the rotator cuff muscles work. The scapula must move with the humeral head in order to maintain a supportive surface. This, in turn, enhances glenohumeral stability and maintains optimal length and tension of the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles. Failure of the periscapular muscles to stabilize and guide the scapula during glenohumeral motion can lead to scapular dyskinesia (abnormal movements). The rotator cuff muscles are generally exercised in conjunction with the periscapular muscles. Gentle stretching of the posterior joint capsule is indicated for tight shoulders. Excessive capsular tension has long been associated with upward migration of the humeral head during shoulder abduction, causing inflammation of the joint capsule, (i.e., frozen shoulder). Shoulder blade stability secured by proper function of the periscapular muscles, balanced rotator cuff muscle strength, and adequate flexibility help maintain normal, healthy shoulder function. The intrinsic rotator cuff muscles are important and offset some of the potentially destabilizing and damaging forces created by the larger extrinsic muscles. The rotator cuff muscles’ oblique line of pull creates downward and inward compression forces. The forces of the rotator cuff muscles and of periscapular muscles maintain the humeral head’s center of rotation. The glenoid labrum, a fibrocartilaginous ring, attaches around the rim of the glenoid cavity and increases the depth of the articular surface. It augments the rotator cuff’s stabilizing effects. Experimental removal of the glenoid labrum has led to a 20 percent reduction in shoulder stability in cadavers.

Conclusion

Rotator cuff injuries to the shoulder are common, painful, and debilitating. Many arm and shoulder movements, especially the overhead movements, are made possible by the concerted actions of four small muscles in the rotator cuff group and the structure of the shoulder joint. Understanding the biomechanics, anatomical structure, and function of the shoulder and of the rotator cuff muscles can assist health care professionals in establishing a better rationale and understanding for selecting specific techniques and exercises for patients and clients in both rehabilitation and injury prevention.

* * *

Dr. Richard J. Vahl

is a former professor and department chairman at the Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa. He is an Adjunct Emeritus Professor on the ICA Council on Fitness and Sports Health Science. In addition to his DC degree, he has a Ph.D. in Health, Physical Education and Sports Science. He is a diplomat of the American Academy of Pain Management and a fellow in Applied Spinal Biomechanical Engineering. Dr. Vahl is a Certified Master of Fitness Science and Sports Science by the International Sports Sciences Association (ISSA). He has published and lectured both nationally and internationally and is a member of the National Association for Sport and Physical Education (NASPE) and the National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM). He has been a team doctor for many state, national, and international sporting and martial arts events and has been the team doctor and medical advisor for the USA Kendo Team and Team Miletich Fighting Arts.

James B. Vahl, BSc, DC,

is a graduate of San Diego State University (SDSU) in Pre-Professional Health Care, Molecular Biology and Sports Medicine. Following a career as a published DNA researcher for Applied Bio Systems, Dr. Vahl earned his Doctorate of Chiropractic with special high honors from Palmer College of Chiropractic in Davenport, Iowa. He is a Certified Practitioner in Active Release Techniques (ART), GRASTON Technique, and Extremity Injuries. He is also a Certified Professional Health and Fitness Specialist by the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and a Certified Physical Trainer by the American Council on Exercise (ACE). Dr. Vahl is a member of the National Academy of Sports Medicine (NASM), and he is in private practice at Vahl Chiropractic Wellness & Sports Injury Center in Encinitas, CA.