by Thomas Kurz

This article covers requirements 2, 3, 4, and 5 for instructors. Requirement 1 is covered in the previous article.

2. Rise from a side split to a six-step horse stance while holding a weight equal to one-third the instructor’s body weight.

This is not very difficult—sitting in a full side split one has to slightly flex the hip and knee joints, then lift the weight off the floor, holding it in both hands in front of oneself at waist level or higher, while rising from the split to the horse stance. The greater the flexion of the hip and knee joints, the easier it is to get up. I show the leg action in a video below.

3. Perform a back bridge.

In a correct back bridge knees are kept behind the line of toes. Whether the instructor can or cannot perform such a bridge, the instructor must show an understanding of common limitations and postural defects and the ineffectiveness of usual exercises as means of removing those limits. This is to make the instructor humble and keep from attempting to overcome these limitations and postural defects by doing more strenuous exercises instead of consulting with a physical therapist (more about it in requirement 6).

4. Know the kinds of flexibility.

There are six kinds of flexibility, with classification depending on the character of the muscles’ action and on the presence or absence of an external force that aids moving through the range of motion or assuming and maintaining a stretched position. Definitions of all six kinds of flexibility are in Stretching Scientifically. Practically speaking, however, in training practice three kinds of flexibility are usually deliberately developed—dynamic active, static active, and static passive below the pain threshold. Following are definitions of these three kinds of flexibility:

Dynamic—The ability to perform dynamic movements within a full range of motion of the joints. High kicks are a display of dynamic flexibility.

Static passive—The ability to assume and maintain extended positions using your weight, like in splits, or using strength not coming from the stretched limbs, such as lifting and holding a leg with your arm or by other external means.

Static active—The ability to assume and maintain extended positions using only the tension of the agonists and synergists while the antagonists are being stretched. One example is lifting the leg and keeping it high without any support.

For more on these three kinds of flexibility, read the articles at the links below.

https://stadion.com/kinds-of-flexibility-and-the-right-role-of-splits-in-taekwondo-karate-and-kickboxing

https://stadion.com/right-stretches-for-high-kicks-with-no-warm-up

5. Know the correct place of flexibility and strength exercises in a single workout and in long-term training.

Don’t do static stretches in a workout before dynamic stretches, kicking, or any other dynamic movements. Dynamic actions benefit from dynamic warm-ups, not from static stretches. For several seconds following any type of static stretch you cannot display top agility or maximal speed because the muscles are less responsive to stimulation—your coordination is off. Maximal force production is impaired for several minutes after strenuous static stretching. This was shown by several studies quoted in Stretching Scientifically. If you try to make a fast, dynamic movement immediately after a static stretch, you may injure the stretched muscles. For all these reasons, doing static stretches before a workout that consists of dynamic actions is counterproductive. The goals of the warm-up are increased alertness, improved coordination, improved muscle elasticity and contractibility, and greater efficiency of the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. Static stretches, isometric or relaxed, just do not fit in a warm-up. Isometric tensions will only tire athletes and decrease their coordination. Passive, relaxed stretches, on the other hand, have a calming effect and can even cause drowsiness.

This caution applies to a single workout and not to long-term training. Long-term stretching programs, with static stretching done at the end of a workout, safely improve flexibility and even strength of the stretched muscles.

For more on the proper sequence of exercises in a single workout and in long-term training, read the articles at the links below.

https://stadion.com/exercises-and-workouts

https://stadion.com/stretching-and-injuries

https://stadion.com/qa-on-training-for-flexibility-and-strength-workout-schedule-1

https://stadion.com/qa-on-training-for-flexibility-and-strength-workout-schedule-2

https://stadion.com/qa-on-training-for-flexibility-and-strength-workout-schedule-3

https://stadion.com/errors-in-training-for-flexibility-in-sports-and-martial-arts

Requirements 6, 7, and 8 are covered in the next article.

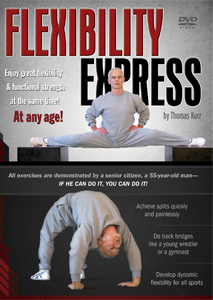

This article is based on the book Stretching Scientifically and the video Flexibility Express. Get them now and have all of the info—not just the crumbs!