by Thomas Kurz

Okinawan te, the precursor of Japanese karate, did not teach high kicks — too risky in self-defense. But high kicks were used in la savate (or la boxe française), a part of the French military’s close-combat training, which French instructors taught to Japanese military during training missions between 1872 and 1919. This is the most likely source of high kicks and roundhouse kicks, which Funakoshi Yoshitaka, son of the founder of Shotokan karate, Funakoshi Gichin, introduced to karate between 1936 and 1945 (see Why and Since When Are High Kicks in Karate?). La savate was a regulated sport since 1820, long before it was brought to Japan, so high kicking in la savate was not as risky for kickers as it would be in self-defense.

Forms (practice patterns of movements) of Okinawan te do not include roundhouse kicks, let alone high roundhouse kicks. It is easy to understand why high-level roundhouse kicks and mid-level (mawashi-geri-jodan and mawashi-geri-chudan) are not included — these kicks expose the kicker’s centerline, so counters to them are easier than those to mid-level front kicks and side kicks. See the below video showing counters to high roundhouse kicks.

Fight-ending, easy counters to high roundhouse kicks

But it is hard to understand why Okinawan te systems did not include low-level roundhouse kicks — to the ankle, the calf, the knee, and the thigh. I have witnessed such kicks delivered with a fight-stopping effect by fighters who had no training in any Oriental martial art or in la savate (French kickboxing), which suggests that low roundhouse kicks come naturally in fisticuffs.

By the way, if you want to see an authentic Chinese kung-fu’s roundhouse kick, done with a sensible form at a sensible target, see this:

Kung-fu roundhouse kick tutorial

Typical Okinawan te combinations consist of a block or a deflection of an opponent’s punching arm, an immediate catch of the arm, followed by a strike to the upper body or a kick well below the opponent’s waist level. Great strength of the grip is fundamental for effectiveness of such combinations, consequently much training time is dedicated to strengthening the grip. Control of the opponent’s arm, and thus of the whole body, with a crushing grip, combined with a side-step off his centerline, makes the follow-up strikes or kicks hard to defend against.

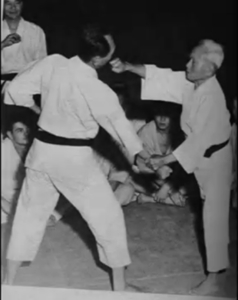

A typical Okinawan te combination demonstrated by Funakoshi Gichin

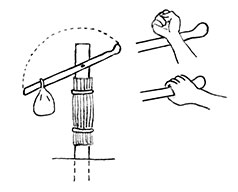

And here is an Okinawan training device, called kakete-biki or kakiya, for practicing such combinations:

Kakete-biki, also called kakiya (click here to see it used)

In such Okinawan te combinations, that are recorded, the kicks are either low front kicks or low side kicks. I have not seen a roundhouse kick in any Okinawan te form. However, a low roundhouse kick to an opponent controlled with a vise-like grip, seems like a natural thing to do, so perhaps these kicks were done, but were not believed to be as tactically reliable as front kicks and side kicks, and so not included in forms. Or, perhaps modernizers of karate (Funakoshi Yoshitaka and his followers) were so enamored with la savate’s roundhouse kicks (click here to see why) that they forced them into Okinawan te tactical combinations, with resulting body contortions. How else to explain the Shotokan karate’s demos of the mid- and high-level roundhouse kicks done while gripping an opponent’s wrist?

Roundhouse kicks done while gripping an opponent’s wrist as demonstrated by Masatoshi Nakayama, famous Japanese master of Shotokan karate, student of Funakoshi Gichin and Funakoshi Yoshitaka

So how come high roundhouse kicks are in so many martial arts? Because these martial arts are really sports, and in sports, with rules and referees, fighters can do things that are too risky for self-defense, where there are no rules.

There is a tactically sound way of doing high kicks, including the high roundhouse kick, in self-defense, and you will learn about it in the next article.

High Roundhouse Kick—Correct Form (for full instruction see Clinic on Stretching and Kicking)