by Thomas Kurz

In this installment on how strength training relates to sports skills, I will continue with jumping ability, which is a manifestation of explosive strength in the form of a jump. Other manifestations of explosive strength are martial arts kicks and punches, or the action of the arm in shot put. The greater the force you can apply in the short time of contact with the ground (jump takeoff), or in the time it takes to throw your martial arts kick or punch, the greater is your explosive strength. The height of your jump depends on how much force you can apply in the short instance of a takeoff. How far your opponent will fly across the ring depends on how much force you transfer to his or her body in the instant your fist or foot contacts it.

The principles of training for jumping ability (but not the particular exercises), also apply to any explosive strength training.

Explosive strength is developed by overcoming resistance in very fast movements, such as by doing very fast squats, throwing medicine balls, jerking dumbbells and barbells, and jumping. But your first task may be an increase in your maximal strength by standard resistance exercises. Decide by answering this question: Is your maximal strength much lower than that of leading athletes who display adequate explosive strength in your sport and in your weight class? If yes, then you may have to first increase your maximal strength.

Zatsiorski (1995), with the example of a beginner shot-putter, explains why someone lagging in maximal strength may increase explosive strength by increasing maximal strength. The delivery phase in shot put lasts from 0.15 to 0.18 seconds, and the best shot-putters (with results of 21.0 m, or 69 ft.) within that short time apply a force of up to 60 kg, or 132 lbs. The best shot-putters bench-press from 220 to 240 kg, or 480 to 530 lbs., which gives 110 to 120 kg, or 240 to 265 lbs., per arm, so you see that in the very brief time available they can use only about 50% of their maximal strength.

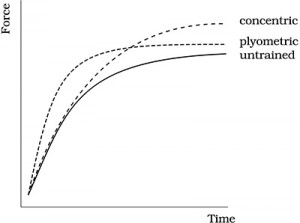

According to Zatsiorski a beginning male shot-putter who bench-presses only 50 kg, or 110 lbs., may improve shot put performance when he bench-presses 150 kg, or 330 lbs. Improvements of maximal strength up to that point may increase the amount of force the athlete can mobilize within the time span of 0.15-0.18 of a second. (The underlying reason is that the strength-time curves depicting the strength increase for different amounts of resistance are identical for the same athlete, so the initial buildup of maximal strength increases force available at progressively longer time intervals—in the case of shot put, up until 0.18 of a second. See “Sports Skills and Strength Training, Part II” for explanation and drawings of such curves.) Eventually an athlete’s maximal strength increases so much that all the curve increase happens later than the time available for action. Further increases of maximal strength probably will bring no improvements in shot put. From that point on, the key to improvement lies in shifting the curve by explosive strength exercises, including plyometrics.

In plyometric exercises muscles are rapidly stretched right before contracting. Examples of plyometrics are jumping drills, depth jumps, clap push-ups, and catching and immediately throwing back a medicine ball.

How strength improves as a result of (a) plyometric, and (b) concentric, or standard strength exercises (Platonov 1997)

Now, on with developing explosive strength for jumps or jumping ability.

If you don’t jump as high or as quickly as you need, even if you can squat with a heavy weight (150-200% of body weight), you should consider adding exercises for explosive strength to your workouts. To tell what exercises you need to focus on, ask yourself if the height of your reach jump from standing still is less than that of athletes in your sport, who jump well and who squat the same as you. Ask yourself how your takeoff for your typical jumps feels. Is it instantaneous and explosive, or is it sluggish? (A very poor result would be 21.6″ [55 cm] for men and 16.9″ [43 cm] for women.)

Poor results in a reach jump done from standing still indicate low explosive strength, especially if your maximal strength in a squat (as measured by maximal weight lifted) is high. Short sets of squats and half-squats performed very fast develop the explosive strength of your legs.

If you have good results in a reach jump done from standing still, but exhibit a long support phase during takeoff in your sports technique, this calls for plyometrics. Plyometrics shorten the time of switching from an eccentric muscle action (a landing or a stomp preceding a takeoff) to a concentric action of the takeoff itself. As the Part II of “Sports Skills and Strength Training” explained, jumps preceded by a short step or a jump (landing and immediately jumping again) require and perfect reactive strength and starting strength. Practicing jumps from standing still does not require reactive strength—the ability to mobilize one’s strength very quickly. Neither does it put as short a time limit on the takeoff as the jump “from a landing,” and so it does not improve the ability to mobilize one’s strength very quickly (Wazny 1981). Practicing jumps “from a landing” increase the height of a jump from standing much more than the other way around.

Both jumps and very fast squats and half-squats develop explosive strength and both types of exercises should be used in training for jumping. Fast squats and half-squats are less intensive efforts and put less stress on the body than full force jumps and depth jumps, however, and therefore should constitute the bulk of your work on developing explosive strength. (Except when your explosive strength as measured by the reach jump is fine but the takeoffs are too long.) Even though your initial progress is faster, a more intensive exercise leads sooner to plateauing or possible regress caused by overwork or injury. One of the causes of plateauing is repeating an exercise numerous times with maximal speed, which results in “learning” to move with that speed such that eventually you cannot exceed it even though your physical potential may increase thanks to other exercises. The more intense the stimuli, the quicker the learning—that’s the principle. This is one of the reasons it is preferable to derive as much benefit as possible from less intensive exercises and use the most intensive ones for the “final touch.”

Children should develop strength with jumps, throws, and body weight exercises, and not with heavy external weights (Drabik 1996). This is not contradicting the principle in the preceding paragraph because children should do only low intensity jumps (from age 7, rope skipping; between 13-15, hopping in place and simple bounding according to Bompa [1996]).

Practice has shown that having reached a certain magnitude of maximal strength is necessary for the safe use of plyometric exercises in explosive strength training. For your legs, you should have enough strength to do a squat with a barbell weighing at least 150% of your body weight (Baechle 1994). Platonov (1995, quoting Gambetta) states that, before undertaking single leg jumps, you should be able to do five squats on one leg, and before starting depth jumps followed by a jump up, you have to be able to do squats lifting at least 200% of your body weight. Before introducing plyometric exercises for your arms, you should be able to bench press from 100% to 150% of your body weight—athletes who weigh more than 115 kg, or 250 lbs., ought to lift 100% of their body weight and lighter athletes ought to lift more (Baechle 1994).

Introduce plyometrics into your training gradually. Start with such low intensity exercises as jumping rope, hops-in-place, and clap push-ups. Progress through more intensive bounds, jumps, and medicine ball catches to high intensity plyometric exercises, such as depth jumps, reactive jumps, and swinging suspended heavy weights with your arms.

Bompa (1996) states that it can take four years for young athletes to gradually arrive at being able to do high intensity plyometric exercises safely.

Progressions of plyometric exercises for 32 major sports and martial arts are shown in Explosive Power and Jumping Ability for All Sports. In this book there are 156 plyometric exercises arranged in sequences specifically designed for each of these sports and 21 supplementary strength exercises to be used in preparation for plyometrics.

In the next instalment you will learn about the methods of performing explosive strength exercises, and about the selection of plyometric exercises.

References

Baechle, T. 1994. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Bompa, T. 1996. Power Training for Sports: Plyometrics for Maximum Power Development. Oakville, Ontario: Mosaic Press.

Drabik, J. 1996. Children and Sports Training. Island Pond, VT: Stadion Publishing.

Platonov, V. N. 1997. Obshchaya teoriya podgotovki sportsmenov v olimpiyskom sportie. Kiev: Olimpiyskaya Literatura.

Tidow, G. 1990. “Aspects of strength training in athletics.” New Studies in Athletics 1.

Wazny, Z. 1981. “Skocznosc.” In Teoria i metodyka sportu, ed T. Ulatowski. Warszawa: Sport i Turystyka.

Wazny, Z. 1992. “Sila miesniowa.” In Teoria sportu (Trening n. 1/13), ed T. Ulatowski. Warszawa: Sport i Turystyka.

Zatsiorski, V. M. 1995. Science and Practice of Strength Training. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

This article is based on the book Science of Sports Training: How to Plan and Control Training for Peak Performance. Get the book now and have all of the info—not just the crumbs! Order now!

If you have any questions on training you can post them at Stadion’s Sports and Martial Arts Training Discussion Forum