by Thomas Kurz

In this article, I answer some questions on strength exercises from readers of my articles, my books, and my videos. Some of these questions are typical, asked by many people, and some are not but answers are educational nevertheless. Some ask about the rationale behind doing exercises in a certain way, others ask inane questions instead of grabbing the weights and trying, working their way up from light to heavy—as if the weights were some toothy creatures that could bite them.

Question: Why do you advise doing long sets of exercises with low resistance as a preparation for low-repetition and high-resistance strength exercises and isometric stretches?

Answer: To increase the structural strength of the muscles so they are less likely to be excessively damaged by strenuous exercises. (Excessive muscle damage announces itself as delayed-onset muscle soreness, or a muscle strain, even a complete muscle rupture.) If the muscles are not structurally strong enough for the efforts asked of them, they become sore or even strained.

Structural strength of a muscle is determined by the strength and cross-sectional area of the slow-twitch muscle fibers and by the strength of the connective tissue within the muscle. Slow-twitch muscle fibers have relatively greater structural strength than fast-twitch fibers, especially the fast-twitch fibers with low oxidative capacities (Fridén and Lieber 1992; Lieber and Fridén 2000). It takes more force to stretch, and ultimately to rupture, the slow-twitch fibers than the fast-twitch fibers. This is because the slow-twitch fibers are smaller than the fast-twitch fibers and have a greater ratio of cellular scaffolding to the contractile elements (which are built of long, thin proteins that are easy to tear). Several studies have shown that muscles with higher ratios of fast-twitch fibers to slow-twitch fibers are easier to damage or tear than muscles with lower ratios (Gleim and McHugh 1997; Jonhagen et al. 1994; Smith 1994).

Endurance training, that is, doing many repetitions per set against low resistance, increases structural strength of slow-twitch muscle fibers (Gleim and McHugh 1997). Such training also increases the structural strength of the connective tissue within the muscle, probably through the anabolic action of hormones that are delivered to the muscle with the increased blood flow (Tipton et al. 1975). The connective tissue damage is considered another one of the causes of delayed-onset muscle soreness (McArdle, Katch, and Katch 2012).

Question: Your article “Beginning Strength Exercises for Abdomen and Lower Back,” advises to use sit-ups to strengthen the abdominal muscles. But many people advise against them because they don’t stress the abdominal muscles much. The first 30 degrees of motion they would compete with the hip flexors, and beyond that, the hip flexors would take over completely. And because the hip flexors are very strong, they would end up doing most of the work, leaving your lower abs relatively undertrained. As a result, you would get a strength imbalance between your lower abs and upper abs, which can lead to injury. I would like to hear your opinion as an expert on this topic. Also, I wanted to know if the oblique muscles require exercise when preparing to start a martial art or if their stabilization function when doing crunches and sit-ups is sufficient?

Answer: Answers to your questions are in the article you refer to. (See the article “Sequence of Conditioning Exercises for Fighters and Martial Artists” and the article “Beginning Strength Exercises for Abdomen and Lower Back.”) Here is what I wrote there: “. . . gradually strengthen your trunk, starting with strengthening the muscles of the abdomen by crunches, then progressing to sit-ups . . . . When your abdomen and hip flexors have good endurance (when you can do a set of 500 sit-ups without extra resistance) . . . .” So it should be obvious that (a) first the abdomen muscles are strengthened with crunches and (b) the sit-ups are for strengthening both the abdomen muscles and the hip flexors. I also wrote, “If your abdomen does not feel weak during 10–15 repetitions of bench extensions with extra weight of 1/3 of your body weight . . . then it should be strong enough for more intense hip flexor exercises [more intense than sit-ups]—lying leg raises without weights”—which shows that the progression of hip-flexor exercises starts with sit-ups. If someone wants to jump from abdomen crunches directly to leg raises I do not mind—it is not going to be my problem.

Regarding the oblique muscles of the abdomen, the answer to your question is this: “When the straight abdomen crunches become too easy, you can do them with a twist. As you raise your shoulders off the ground, raise your bent right leg and twist your trunk to touch the left elbow to the right knee and then with the next raise, twist the other way.”

Question: I would like to know how many sets you advise for bench extensions (a set with 30 reps).

Answer: As many as it takes for you to feel improvement. My experience says 2–3 sets are enough.

Question: I am a practitioner of Taekwondo and have a question concerning a statement made on your video Secrets of Stretching and in one of your articles. You state that leg exercises are to be added to the strength routine when one can perform 3 sets (10–15 reps) of back extensions on the bench with additional weight greater than 1/3 of the body weight. If I interpret this statement correctly, then for example, a 150 lb. person would add leg exercises to the strength routine when they are able to do 3 sets of back extensions on the bench using 50 lb. of weight. Is this the correct interpretation? If so, then since I weigh about 150 lb. that means I would have to lift an extra weight of 50 lb. This is a huge amount of weight, and it seems to me that only professional bodybuilders would strive for such a goal. I am concerned that 1/3 of the body weight is too heavy for this type of exercise and could subject one to high risk of back injury.

Answer: Your interpretation is correct and your dread of the 50 lb. is pathetic. You practice Taekwondo, a martial art, but have no concept of the “martial” nor of the “art.” Martial means related to war and characteristic of a warrior—now, it doesn’t sound very warrior-like to kvetch even before starting to prepare for the goal. Art implies striving for perfection and pushing one’s limits. If at 150 lb. you see 50 lb. as a huge and intimidating weight, you are not driven and have no warrior in you.

In this exercise, one should be able to lift additional weight greater than 1/3 of the body weight before attempting strenuous hip flexor and adductor exercises. If you cannot do this and attempt the hip flexor and adductor exercises, you risk injury (sudden or gradual) to the lumbar spine. As the weights used in hip flexor and adductor exercises increase so should the loads strengthening your lower back. For example, I weigh 155 lb. and I lift 90 lb. in back extensions on the bench, 130 lb. in the “good morning,” and 300 lb. in the deadlift because I do adductor flys with substantial amounts of iron on my ankles.

Back injuries are a result of insufficient strength of the moving and stabilizing muscles (the result of wimpy attitudes toward back training), neurological deficiencies, structural problems, and poor exercise technique.

Question: In your articles and in your video Secrets of Stretching, you give guidelines on the required foundation of back strength before beginning squats, using extensions on a bench for the test. As I don’t have access to the appropriate sort of bench, could you give me guidelines using deadlifts? I am currently deadlifting my body weight in 3 sets of 12; is that adequate to safely begin squats?

Answer: To begin, yes.

Question: I know you recommend deep and heavy squats for leg strength. I train at home and don’t have a spotter; nor do I have time to go to a gym. I’m a kickboxer and would like to improve my leg strength for use in my sport, and I was wondering what alternative to very heavy squats I might use, seeing as how it’s not feasible to squat heavy without a spotter. Are there other exercises I could do that would produce a similar level of leg strength?

Answer: Squats and deadlifts are the easiest lifts to self-spot. If you need a spotter for a squat, then you are lifting too much—especially in that you are a kickboxer and not a powerlifter. A person who trains progressing gradually can self-spot squats with the help of a rack or, in emergency, can easily dump the bar weighing more than one’s body weight.

Question: Every time I do squats, and sometimes deadlifts, my inner thighs get very sore. This soreness lasts for about 2–3 days and interferes with my martial arts, stretching, and running workouts way too much. I have noticed that sometimes my knees bow inward and wobble a little bit when I do squats. I have been working with weights for several years and have good quads, but something is definitely wrong here. Do you have any suggestions?

Answer: It seems that the loads you lift in squats and in deadlifts are exceeding limits of what the muscles of your inner thigh can adapt to. The load (resistance) in any exercise must be determined by the weakest link in that exercise—otherwise injury happens, either right away or after recurring muscle soreness.

You say that you “have been working with weights for several years and have good quads.” I suspect that you took up squats and deadlifts recently and up to now you have been doing isolated exercises for the quads and this is why your thigh muscles are not proportionally developed.

I suggest that you either reduce to the minimum resistance in squats and deadlifts and gradually work your way up to your normal weights, or lay them off temporarily and in the meantime selectively strengthen muscles of your inner thighs. Such exercises are shown on the video Secrets of Stretching because strengthening the inner thigh muscles is the key to doing splits.

There are many more questions, but these are enough for this article.

This article is based on the book Science of Sports Training and the video Secrets of Stretching. Get the book and the video now and have all of the info—not just the crumbs! Order now!

References

Fridén, J., and R. L. Lieber. 1992. Structural and mechanical basis of exercise-induced muscle injury. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise vol. 24, no. 5 (May), pp. 521–30.

Gleim, G. W., and M. P. McHugh. 1997. Flexibility and its effects on sports injury and performance. Sports Medicine vol. 24, no. 5 (November), pp. 289–299.

Jonhagen, S., G. Nemeth, and E. Eriksson. 1994. Hamstring injuries in sprinters. The role of concentric and eccentric hamstring muscle strength and flexibility. American Journal of Medicine vol. 22, no. 2 (March–April), pp. 262–266.

Kurz, T. 2004. Secrets of Stretching: Exercises for the Lower Body. Island Pond, VT: Stadion Publishing Company, Inc.

Lieber, R. L., and J. Fridén. 2000. Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle and Nerve vol. 23, no. 11 (November), pp. 1647–66.

McArdle, W. D., F. I. Katch, and V. L. Katch. 2012. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Smith, C. A. 1994. The warm-up procedure: To stretch or not to stretch. A brief review. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy vol. 19, no. 1 (January), pp. 12–17.

Tipton, C. M., R. D. Matthes, J. A. Maynard, and R. A. Carey. 1975. The influence of physical activity on ligaments and tendons. Medicine and Science in Sports vol. 7, no. 3 (Fall), pp. 165–75.

Another great no nonsense article, its hard to find evidence or experience based information on the internet for martial arts training. Stadion.com has become one of my go to sources.

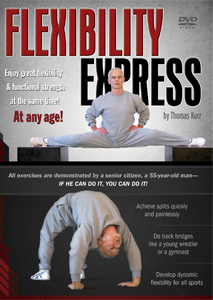

Thank you for providing this free information, also thank you for your Flexibility Express DVD, it is simple yet effective programming.

Regards,

Chris, Melbourne, Australia

I absolutely love the no nonsense answers given here. Keep it up! :-))

I know that sprinters shloud do stuff like squats and big weight exercises like that, and that long distance runners shluod do exercises like hills to build muscle but I was wondering what kind of weightliftibng exercises would be good for a mid-distance (800m) runner? I’ve been doing lunges, step-ups, leg press, leg extension, leg curls and calf raises. Are any of these a bad exercise to use, and what would be a few good exercises to do? Thanks a lot.