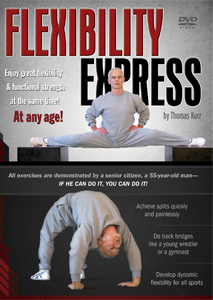

by Thomas Kurz

This continues the refutation of misconceptions and errors in the quote from Charles I. Staley. (See the first part or the second part of this article.)

Why do you need aerobic fitness for “anaerobic” sports?

To get the skill you need to drill. No drill—no skill. The faster you recover between the drills the more you can drill. This is the reason for developing aerobic fitness, which determines how fast you can recover.

Zbigniew Czajkowski, a teacher of coaches and a world-class fencing coach himself, who trained medal winners at world championships and the Olympics in foil, épée, and sabre, says: “In sports in which short, speed-type, high-energy-cost efforts are characteristic, one ought to do a lot of exercises stimulating anaerobic metabolism. Of course, every excess may lead to nonsense—and in those sports it is necessary to do a certain minimum of aerobic exercises, because:

“1) a certain level of aerobic fitness (in some sports not very high) is a foundation of general fitness [and thus of health];

“2) some actions during a fight demand aerobic energy; and

“3) maintaining a certain level of aerobic fitness is necessary for timely recovery after effort” (Czajkowski 1997).

Passive rest after an intense anaerobic workout may not be the fastest way to recover. A light aerobic effort, below the anaerobic threshold (McArdle, Katch, and Katch 1991, Wawrzynczak-Witkowska 1991), preferably of different character and in different surroundings than your regular workout, speeds up recovery and refreshes you mentally.

You need to train first to be fit for training before you train for competition. Lev Matveev, the researcher who systematized the concept of periodization, points out that endurance requirements for competition are not exactly the same as for training. To progress, the athlete must perform greater efforts in training than during the competition. Volume of sport-specific loads may increase in the course of a few years tenfold and more, while in several sports the duration of the competitive event may remain the same—for example, the duration of a match, or the number of rounds. The volume of training loads must also increase to improve time for covering distance (Matveev 1981).

Increasing aerobic endurance—the ability to supply tissues with oxygen during work—increases the intensity of efforts at which energy is produced anaerobically with resultant buildup of acids in body fluids. The higher aerobic endurance, the later fatigue occurs (or at the higher intensity of effort) and the longer techniques can be “sharp and crisp.” During a boxing round, periods of high activity, such as a series of punches, are followed by short periods of lowered activity. During these periods, when boxers prepare their next attacks, they relax and move differently than during the attack, they breathe heavily, oxidizing the buildup of lactate (an ester of lactic acid), product of the anaerobic metabolism, and this lets them recover partially. This aerobic recovery mechanizm explains the relatively low concentration of lactate in boxers’ blood after matches (Dziasko et al 1982).

Boxers during fights generate a great oxygen debt and, if they are in good shape, very effectively “pay it back” afterwards. Their readiness for a next round during a match, and for a next fight during a tournament (or for a next workout) depends on their speed of recovery, which depends to a great degree on their aerobic fitness.

Click here to read “The Role of Aerobic Fitness in High Intensity Efforts, Part IV.”

References

Czajkowski, Z. 1997. “Chodzeniem wokol stolu nie poprawi sie umiejetnosci gry w bilard.” Sport Wyczynowy no. 389-390: 111-113.

Dziasko, J., Kosendiak, J., Lasinski, G., Naglak, Z., Zaton, M. 1982. “Kierowanie przygotowaniem zawodnika do walki sportowej.” Sport Wyczynowy no. 205-207: 3-65.

Matveev, L. P. 1981. Fundamentals of Sports Training. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

McArdle, W. D., Katch, F. I., and Katch, V. L. 1991. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Wawrzynczak-Witkowska, A. 1991. “Znaczenie odnowy biologicznej w procesie treningowym.” in Waldemar Tlokinski ed. 1991. W kregu psychofizykalnych zagadnien profilaktyki i terapii w sporcie. Gdansk: AWF Gdansk.

If you have any questions on training you can post them at Stadion’s Sports and Martial Arts Training Discussion Forum